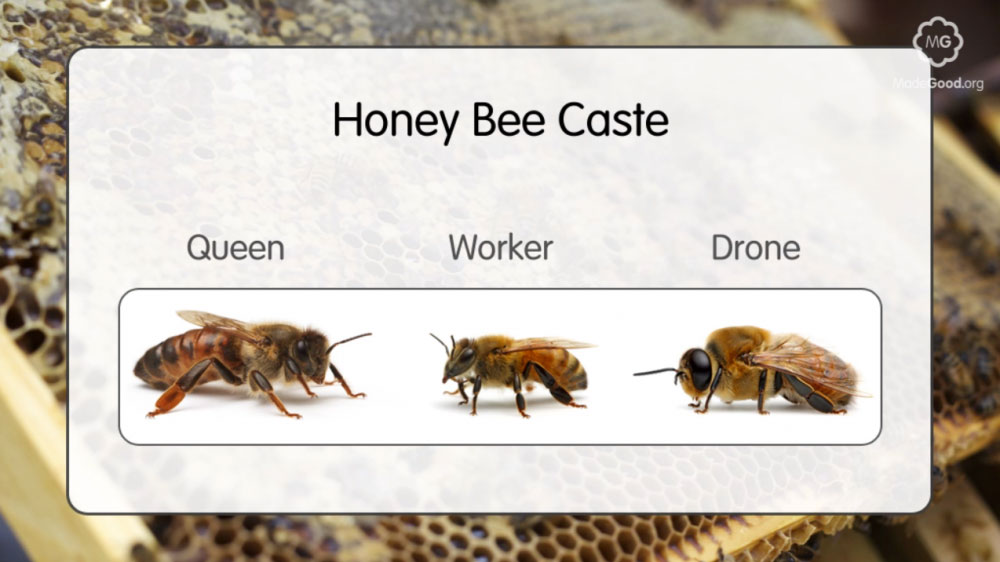

Honey bees are extraordinary creatures. Like humans, they live in groups, enjoy each other’s company, and work together to achieve common goals. Unlike humans, they are eusocial. This means the individual bee is part of a caste, or type, of bee: either the “worker” or non-reproductive caste, or the “royal” or reproductive caste. Bees in the worker caste perform the different jobs necessary for the proper function of the hive and survival of the brood (eggs and larvae). Bees in the reproductive caste do what they need to do to make more bees. Unlike the balance of female and males we have in human society (almost one to one), most of the bees you see within the

Image I: This is an example of each cast of bees: starting from the left is the queen, the worker, then the drone. http://www.madegood.org/beekeeping/honey-bee-caste/

WonderLab display hive are female. The queen and all workers, which make up the vast majority of the bees you see in the hive, are female. Only drones, the extra-large and somewhat rounded looking bees, are male. This condition of having groups of bees that look different within the same species is known as polymorphic.

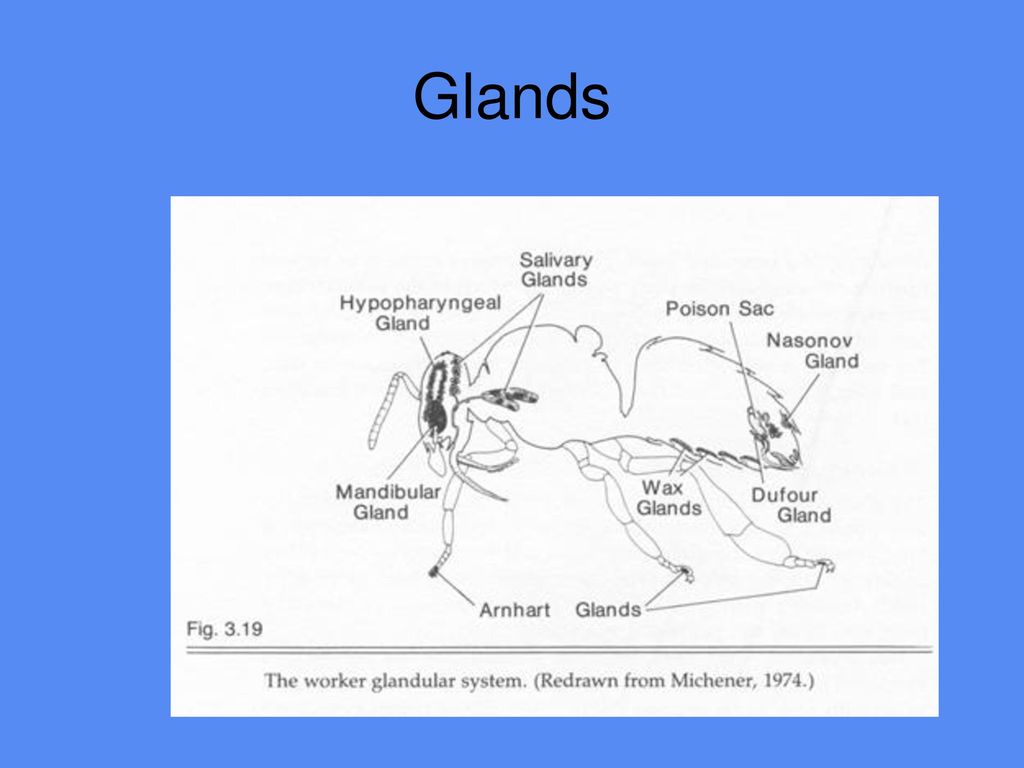

Worker bees do the jobs needed to maintain the hive, and they work all day and night. The jobs they perform vary depending on the age of the workers, the time of year, and how many workers are currently doing a particular job. A worker’s body has specially made parts to aid her in her job. Young adult workers are responsible for tending to the queen and her eggs, larva, and pupa – or the “brood” as they are collectively called; these workers have glands in their head (hypopharyngeal gland used to make “bee milk” to feed these young. Other workers are responsible for building and repairing the wax honeycomb that makes up their hive; these workers extrude wax from glands on their abdomen (belly) to mold into comb. The older adults have the more dangerous jobs like leaving the hive to collect the resources needed to make the hive’s food: flower nectar and pollen. And all the bees work together to guard the hive from invading bees and other threats to the hive, both big and small. Only so many workers are needed for each job, and they produce a pheromone (smelly chemicals the body lets off) to communicate what job they are doing. Bees move between jobs to ensure every job gets done.

Image II: This image points out all of the glands in a bee body. The two glands mentioned in this article were the hypopharyngeal gland and the wax gland. https://slideplayer.com/slide/12497854/

The drones and the queen are the only members of the “royal” or reproductive castes. The queen bee has the very important job of laying eggs – and is not the head of the hive like one might think by her title as queen. She and her brood are, however, the very heart of the hive. The queen lays two different kinds of eggs: fertilized and unfertilized. Fertilized eggs produce worker bees and, if necessary, the next queen, while unfertilized eggs produce drones. Besides laying eggs, the queen continuously releases pheromones from her body. These powerful chemical cues both recruit and retain the worker bees, ensuring their loyalty to her. This functions as a sort of “glue” that holds them all together.

As of now there have not been any drones spotted within our Hive, and for good reason. The job of a drone is to mate with the queen to help her produce different kinds of offspring and they are normally seen in the spring/early summer or when a hive is about to need a new queen, which the Wonderlab hive does not. Drones are born without stingers, cannot make any honey, and cannot really help with any other job around the hive. They simply mate with the Queen to try to help her make the offspring needed to run bee society and the hive.

The new queen for the WonderLab display hive will arrive in May 2019. We do not know the exact date because we have to wait for our queen to be born and start making brood before we can pick her up. She will be a varroa sensitive hygiene queen, which means she produces offspring that is resistant to the parasitic varroa mite . Follow us on Facebook to find out when her majesty arrives!

About the Authors:

Gabrielle Gilbert was an Animal Exhibits Intern at WonderLab during the summer of 2018. She is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in religious studies and animal behavior at Indiana University. During her time at WonderLab she helped to establish an observational beehive inside the museum. Bees from the hive helped pollinate the Wonder Garden plants and Gabrielle spent many hours talking to visitors about the importance of bees.

Sources:

Leave A Comment