In today’s world, one of the few things we can be certain of is our need for scientists, technology-developers, engineers, and mathematicians. As we say at WonderLab, these individuals work in STEM fields (aka: the fields of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) and their expertise is vital. According to the U.S Department of Commerce STEM occupations grew 24.4% faster than other occupations and STEM workers earn 29% more than non-STEM counterparts. Early exposure to STEM fields is also thought to be crucial to our country’s future economic stability.

Important as they are, STEM fields can be more challenging to switch to mid-way through life. STEM disciplines are most accessible to those who attained some level of STEM learning early in life. Emmy Brockman, the Education Director at WonderLab, says that building the identity of scientists at a young age is one of the most important predictors for whether someone goes into a STEM field. James C Conwell, the president of the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, agrees, saying, “Exposing youngsters to STEM areas in the early grades, keeping that interest alive through exceptional teaching, and ensuring that students take rigorous high school courses, are important strategies for increasing the number of students who will be drawn to STEM professions.”

One of WonderLab’s programs aiming to promote STEM skills is STEM Sunday. These weekly projects challenge not only the children present, but their families as a unit, to solve engineering problems with household items. Families get to build robots, create roller coasters, move objects without touching them, and more. Carl Cook, CEO of Cook Group, helps fund STEM Sundays as a way to encourage more children to learn about STEM fields. An electrical engineer himself, Cook and his wife Marcy have been members at WonderLab for several years.

Carl Cook: Engineer, Weekend Tinkerer

Before Carl Cook earned an MBA from the University of Iowa, he graduated from Purdue University with a bachelor’s degree in engineering. When I spoke to him about his hobbies, Cook explained that although he is an electrical engineer by trade, he often spends his free time “tinkering with old Studebakers and a Buick” that he owns for sentimental reasons.

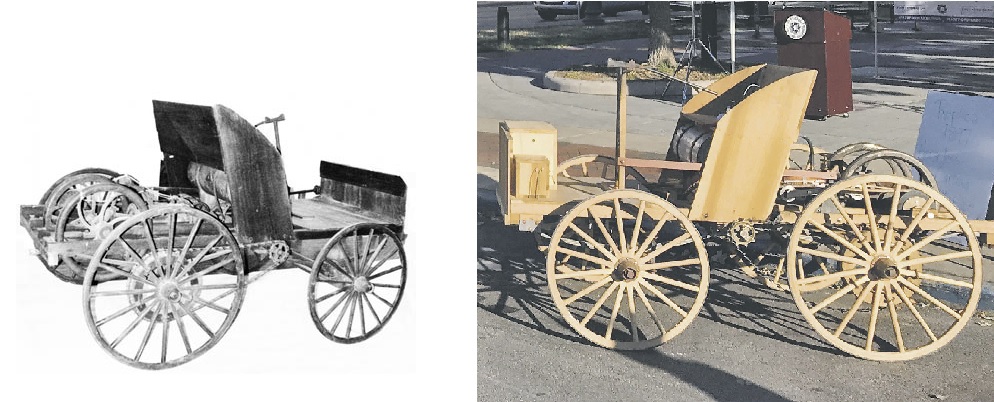

Cook got the idea for the project while attending an exhibit at the Mathers Museum of World Cultures organized by the Stone Age Institute titled “The Big Bang to the World Wide Web: The Origins of Everything.” The Mathers exhibit was an educational project featuring the top 100 events in our universe’s history and included Bloomington’s own, first horseless carriage. Cook decided he would build a replica of that first carriage, originally built by an engineer named J.O. Howe.

Indiana University Anthropology professors, Kathy Schick and Nick Toth, were involved with the Mathers project and asked Cook if it would be possible to get the car up and running again. Cook said it was unlikely, but as a counter-suggestion said they might be able to build an exact replica. Cook took on the project as a challenge. Could it be done? He enlisted mechanical engineer Ronan Young to help.

The First Step is a Doozy

To begin their project, Cook and Young needed to measure and catalogue the various parts used to build the original machine. Unfortunately, the original was delicate in its old age and so the Mathers Museum wasn’t eager to let them touch it. Cook and Young found their solution in technology. The two engineers used a laser imaging device (borrowed from Cook, Inc.) that allowed them to take mathematically precise measurements of the insides of the engine and the rest of the Howe machine without them having to touch it excessively. Technology allowed the project to move forward – although the pair later earned the museum’s trust; they were eventually allowed to physically touch and measure the original carriage.

Cook and Young had been challenged to create an exact replica of the horseless carriage, and that was what they endeavored to do. Unfortunately, this added extra steps – to build it exactly right, they wanted to use techniques and materials that fit the time period. Even more unfortunate was the amount of mystery surrounding the car’s origins. Discovering the truth meant sifting through the numerous false accounts and conflicting stories about the car, most of which were second-hand like the image below.

This image, often touted as Bloomington’s first automobile, is actually a Winton bought by J.O. Howe years after he built and tested his own machine.

According to one, first-hand account from a man named Dick Bierly who actually worked on the original, the first machine was built in 1907. This fact proved incorrect. Even at the time, Bierly’s family conceded that he was getting older and may have gotten the dates confused.

Cook found the truth after spending, by his own calculation, well over 50 hours sitting in the Monroe County Public Library pouring over newspaper microfilm. On June 25, Cook found the words he’d been searching for:

“… last night, the first horseless carriage ever to be operated in Bloomington was tested by JO Howe and he pulled it in front of the jewelry store.” – Bloomington Daily World, June 26, 1897

The morning edition of the Bloomington Daily World was dated June 26, 1897. Cook had found the original article describing the Howe test drive.

Once Cook knew the exact year things fell into place. By studying Bloomington geography from 1897, he and Young reasoned what technologies, methods and materials were most likely used in the project. It was time to move on to the next part of the process – construction.

Parts is Parts

The first big hurdle was the engine. Most of the metallic pieces used by Howe were likely melted down and recast as machine parts that would assist the war effort in the World Wars; many of those pieces were discontinued. Cook and Young would have to build all the new parts by hand. Luckily, Bloomington is home to the Sculpture Trails’ Traveling Foundry. Sculpture Trails is an outdoor museum that features a hiking trail with numerous – you guessed it – sculptures scattered along the way. The Traveling Foundry allows people of all ages to cast and forge metal creations in aluminum or bronze. With the Foundry’s assistance, Cook and Young sculpted casts and poured molten metal to create the pieces needed. The forging process was done almost entirely by hand, which they felt would make the final results closer to what would have been available in the late 1800s.

The original car’s frame was wood, as many automobile makers at the time tended to use this more pliant and easy-to-shape material. The wood used in the replica was supplied by Young, who had obtained it with the understanding that it had come from a barn built in the 1880s. This ensured that the most visible part of the replica was built using time-correct materials.

The wheels used in the original were scavenged from a wagon, so Young and Cook provided their specifications to local Amish carpenters. Once they had the wheels, the engineers even made sure to break one and repair it so that it matched a mended wheel on the original car.

Another hiccup was the fuel used for the engine. Acetylene was commonly used in the late 1880s, so it was Cook and Young’s first choice. They quickly found out, however, that acetylene is too volatile and flammable to be safely used – a lesson learned at the cost of scorch marks across the back of the seats in the car. They changed their fuel to propane, which was an obvious choice as propane is chemically similar to coal gas, another fuel common in the late 1800s.

Pieces to Whole

Cook and Young’s study of the original car began in the gallery in the Mathers Museum on October 24, 2013. They managed to get the engine to start for the first time on September 25, 2016 – though there were some steps left to take. Though the engine managed to turn on in late September, the belt transmission and differential weren’t finished yet. Final assembly was finished by early October, making the project just under three years.

Once the car was finished, Cook and Young couldn’t resist showing it off. They brought it to various car shows throughout the next year or so, but got the venue they wanted about a year later. On September 29, 2017, Kirkwood Avenue was closed down to showcase a driverless bus. To provide contrast, Cook and Young provided their replica of the Howe machine and drove it down the avenue, mirroring the original’s debut while simultaneously highlighting Bloomington’s first and latest automotive advances. It was quite the contrast, given that the replica couldn’t go faster than five miles an hour and nearly shook itself to pieces in the process.

Since then, the replica has occupied a lovely spot in Cook’s garage. It may end up positioned outside the cafeteria at Cook, Inc, although there is a competing offer to place it in the dome at the West Baden Resort in French Lick. The original horseless carriage built by Howe is presently owned by IU, though the Monroe County Historical Center is in the process of trying to get it on loan.

Weekend Scientists and Garage Engineers

Scientific curiosity and knowledge showed Cook and Young to know what fuel to use. Technology granted them access to an otherwise-untouchable original. Engineering helped them hand-craft most of the pieces needed for the machine. Mathematically precise measurements and construction made the entire project possible.

Without STEM, Carl Cook and Ronan Young may never have taken on this project. Without their efforts to rebuild the Howe machine, Bloomington would have forgotten long ago how its very first car worked and how well it ran – which, it turns out, is not very well. But we would never have known without Cook and Young’s dedication to the STEM disciplines.

The J.O. Howe horseless carriage, left, and the Cook Replica, right.

Cook’s project embodies the spirit of what WonderLab has pushed for – the spread and application of STEM fields in day-to-day life. While studying STEM disciplines may lead to a wider range of higher-paying jobs, this shouldn’t just be done for economic security. Cook showed that these areas of study have the potential to enrich our everyday lives, opening doors for us to explore the world around us in a more complete and fulfilling way.

Miranda Barnett is the Mentor Education Intern & ASE (After School Ed-ventures) Co-Leader at WonderLab, and she helps to run the STEM Sundays program.

“A family that comes through fairly regularly came to STEM Sunday one week and worked on a project we hadn’t done before,” says Barnett recounting a recent STEM Sunday experience. “They were building ‘water-color bots,’ similar to our scribble bots, but with smaller pieces. Their son is on the younger end, but they worked together very well as a family to solve the challenge, and even thought about ways to recreate their robot at home. They modeled exactly what we aim to see in STEM Sunday – the parents guided the child in thinking about the task at hand, how to solve it with the materials provided, and let him do most of the work, stepping in to help when needed. Once their robot was built, they made up challenges for themselves, and talked about how to recreate the challenge at home.”

Barnett describes STEM Sundays as providing engineering-based challenges designed to have a family work as a unit to solve a problem. This allows both children and their parents or guardians the chance to build on their STEM skills and learn about each other in the process. More than that, STEM Sundays feature projects that can be recreated with supplies found in the average home, allowing families to continue practicing their STEM skills in the living room as individuals or as a unit.

Through STEM Sundays, WonderLab seeks to help families learn more about the world around them in a practical and enriching way – and by funding it, Cook helps set Bloomington’s young scientists, inventors, engineers, and mathematicians on the path to discovery and success.

The Writer: Samuel Zlotnick is 24 years old and is a self-described “scifi/fantasy geek”. He just began an internship at WonderLab in its Marketing/PR department which he feels will compliment his eventual Bachelor’s Degree in Professional & Technical Writing. With a father in the Biology Department at IU, Sam is only too aware of the importance of Science and Scientific thinking.

Leave A Comment