Corals are able to build the magnificent reefs we see today because of a very important, symbiosis with unicellular, photosynthetic dinoflagellates called zooxanthellae (simply put, they are really small algae). Scientists estimate that coral and zooxanthellae have been working together to make reefs for 200-250 million years (Rohwer, Youle, 2010)! Before we get to that, what does symbiosis mean? What is a unicellular, photosynthetic dinoflagellate?

Symbiosis is a relationship between two species in which both organisms benefit. Think of you and your good friends. Being friends makes you both happy and you both get something good out of having a relationship. In the animal kingdom, this is called symbiosis. Zooxanthellae are unicellular meaning they are composed of only a single cell, photosynthetic meaning they take sunlight and CO2 and make sugar and oxygen, and are dinoflagellates meaning it is a single celled, organism that has . This relationship helps to retain nutrients in a nutrient poor ecosystem. Almost 90% of the nutrients produced by the zooxanthellae is passed on to the host coral, thus wasting very little of the resources produced (Sumich, 1996).

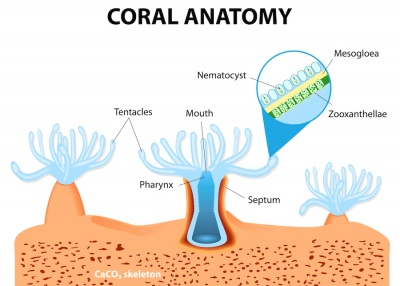

This is a diagram of a coral depicting where zooxanthellae are housed. http://coraldigest.org/index.php/Zooxanthellae caption

The zooxanthellae live within the cells of the soft tissue of the coral. Because of this, the coral provides them with CO2, a protected place to live, water and easy access to sunlight. They have nearly unlimited photosynthesizing power but itty bitty living space, so tiny in fact that 1-5 million can fit into 1 cm2 (Pechenik, 2015)! Because they live within the individual cells of the coral, their access to organic nitrogen is limited and so their growth is as well. This lack of nitrogen restricts their growth rate, however, they produce huge amounts of sugar, more in fact than is necessary for their own survival and reproduction. This excess sugar is actively passed from the zooxanthellae to the coral and is then used by the coral to create their calcium carbonate skeletons. Current studies suggest that coral get about 95% of their energy needs from this Zooxanthellae (Falkowski et al., 1984). Without this symbiont, corals cannot continue to live in their current habitats as they have no way of making their skeletons and building reefs.

Zooxanthellae can be expelled from the coral when a stressor is present. A stressor is a change in some factor the coral experiences that takes its environment out of the ideal range. For instance, an increase in temperature of only 1-2oC can have devastating effects on the survival of coral as it can cause bleaching and impede skeleton growth (NOAA, 2017 https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/kits/corals/coral02_zooxanthellae.html).

https://www.inverse.com/article/34218-what-is-coral-bleaching-chasing-coral-great-barrier-reef-dead

This side by side shows healthy Acropora cervicornis or staghorn coral (left), bleached staghorn (middle), and dead staghorn (right). This patch made of hundreds of coral took only 8 months to bleach and die.

In 2014, NOAA wrote about an El Nino that never fully formed, but which set of a 3 year, worldwide bleaching event that is the longest and arguably the worst the world has ever seen. As of April of 2017, 93% of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia was estimated to have been bleached (http://www.noaa.gov/media-release/us-coral-reefs-facing-warming-waters-increased-bleaching). Even U.S. waters saw widespread bleaching in Hawaii and Florida for years now. Bleaching events are are not only getting more intense, but they are coming closer together, decreasing the time coral have to recover.

Fortunately, not all of the world’s corals have bleached in the last few years. Scientists are flocking to these populations to study them to figure out why they were so resistant to the bleaching event in the hopes of getting insight on how to strengthen the rest of the world’s corals. What’s more, at the General Meeting in Paris France, the International Coral Initiative declared 2018 the 3rd Year of the Reef (https://www.icriforum.org/about-icri/iyor). This is a world wide conservational effort to help educate the globe about how important coral reefs are to the safety of our coasts, our global economy and the health of our oceans and to make an impact on the health of our coral. The first one was in 1997 in response to invasive species that were wiping reefs out. In 2008 the second Year of the Reef was established to educate the world about human impact on coral health and now in 2018, we are celebrating the 3rd global movement to save our reefs from the ever growing heat of our oceans.

WonderLab will be involved in this year long movement hosting events, writing literature and generating buzz about the issues our oceans face today. You can get involved by visiting the sources provided in this article to further educate yourself on what is happening. You can begin with small steps like turning electronics off that you are not using, riding your bike or walking instead of using a car, and being careful on what you put down your drains or what fertilizers you use on your lawns. You can also join us throughout the year to celebrate the wonderful gift we have that is our oceans so stay tuned as we will have updates throughout the year.

Sources and further reading:

Rohwer, Forest, and Mary Youle. Coral Reefs in the Microbial Sea. Plaid press, 2010.

Pechenik, Jan. Biology of the Invertebrates. 7th ed., McGraw Hill, 2015.

Advancedaquarist.com

SAM COUCH Writing to you here. I am the animal exhibits manager at WonderLab Museum of Science, Health and Technology. I found my way here from Indiana University where I got a B.S in Biology and a certificate in animal behavior with a concentration of marine science. I have done coral health assessments in the Dominican Republic and studied tropical biology in the Cayman Islands but the most important things you should know about me are that I think coral are one of the coolest animals on the planet (that we know of) but if I could be any animal in the world for a day I would want to be Cuvier’s beaked whale. In 2014 they were logged for the deepest dive, so if I were a beaked whale, I could see first hand where no human can dive!

Leave A Comment